After my previous double update — in case you missed it, here are the links to Brought together 1 and Brought together 2 - go check’m out! — I was visited by two of my best friends. I want to thank both Yoana and Tessa for taking the time to visit me and endure my guiding tour. After they had left, I had to prepare for my fieldwork class. This year Professor Sung Li-May is focusing on Bunun, one of the 15 or so indigenous languages that can be found in Taiwan. They are Austronesian languages, which means they belong to the same language family as Philippine languages, Indonesian languages and many more. They spread out all the way until Hawaii (yes, Hawaiian is an Austronesian language) and New-Zealand (Maori), so it is very probably the biggest language family or the one that covers the biggest territory.

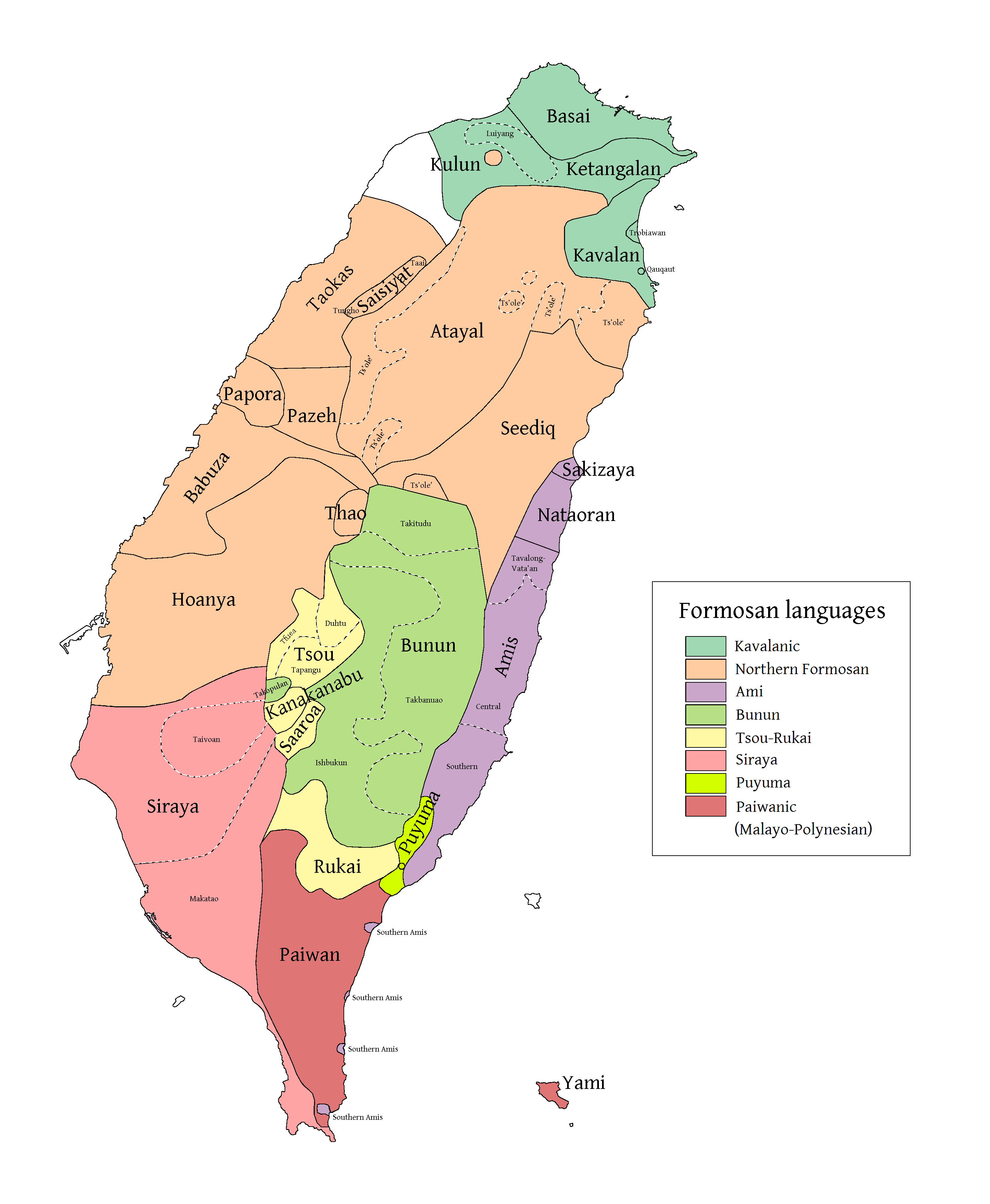

All these languages seem to originate from the island of Taiwan, which is, as you know, the place I am studying. Since this island used to be called Ilha Formosa ‘beautiful island’ by the Portuguese, the subbranch of Austronesian languages that can be found here are known as the Formosan languages — this variation is “Taiwan’s gift to the world”. There is ample archeological evidence that supports the move from Taiwan to the Philippines to the West and then to the East (Bellwood 2000; Oppenheimer 2001). And one of the languages that can be found in this group is Bunun in Taiwan. Above is a map of the places where it’s spoken.

It is spoken by the Bunun tribe, whose massive migration of Bunun started around the turn of the 18th century, i.e. about 300 years ago. The Bunun tribe was originally settled in the midwest of Taiwan, all in Hsinyi county. It dispersed to the south and east. The first subgroup to migrate was Takupulan, which had been resettled to the south of Tsou by the mid-18th century. Then there were two main waves of dispersal: The first to the south and southeast, and the second to the west and southwest, including Isbukun, Takivatan and Takbanuaz subgroups. The latest migration was the northern subgroup, including Takituduh and Takibakha (Li 2004).

They are mostly known for two things: one is the coming-of-age Ear-Shooting ceremony, called malahtania; the other is polyphonic singing pasibutbut. Here is a video of them singing:

Currently there are about 50,000 Bununs still alive (De Busser 2011). They are traditionally divided into five dialects: Isbukun, Takivatan (cf. De Busser 2009 — yes, the specialist on this dialect is Belgian), Takbanuaz, Takituduh, and Takibakha. Taki means ‘from-‘; and the dialect we studied, Isbukun, is also known as Bubukun. It is estimated to mean something like ‘the Bunun people’. And bunun itself just means ‘human’.

The goal of this course, because it is still schoolwork, is to add to the database of Formosan languages that is being developed by my institute. For this we had a teacher every week in our class who we could ask questions to. In this way we elicited more and more language data, for a total of 27 hours. And from 2 June until 6 June we went ‘into the field’ as it is known, to gather more data by talking with three very helpful informants. I will now try to give an overview of our trip:

Day 1

We woke up really early to take the early Highspeed Railway to Zuoying 左營, where we consequently were split in two vans. I must point out that we were about 13 people in total and that the vans were thus very big. We were taken into the mountains. Before I had a lot of expectations and romantized thoughts about the village were bound for, which was called Taoyuan 桃源 (not the one with the airport) in Chinese, or Kavalung in Bunun — “Do they live in normal houses? Is there electricity? Is there internet? Is there water? Do they live in tents? …” What I found was just a normal village in the country/mountainside. They are very modernized, but from what I gathered they still care about their heritage as hunters. So we got to know our informants and started working: asking novel sentences (or reaffirming old ones) in orde to explore the different uses of different bits and pieces of the language. We worked for about three hours per session, a rhythm that would repeat itself in the next few days with about two sessions every day.

We stayed in a few rooms above/behind a church. It is very obvious that the Bunun people we met are a closely knitted community with a lot of adherents of Christianity (there seem to be both Presbyterian and Catholic variants in Kavalung). There were three big rooms and one smaller and eventually I slept in the same room as the teacher because that way I had more space. The last day we were joined by girls who had fled their room because of cockroach problems.

Day 2

Waking up around 7 AM (actually a bit before because my classmates are very active in the morning), we went to a breakfast place which enticed us to become regulars in the few days we were there. Things that happened on this included a confirmation that living in the mountains offers ever-changing beautiful landscapes, so that is what you will get a lot of pictures of.

I also attracted a crowd of young fans who kept calling me ‘america’. They asked me if I came from the US (Meiguo 美國), England (Yingguo 英國), or ‘Abroad’ (Waiguo 外國). The structure of these words in Chinese makes it seem as if ‘Abroad’ really is a country. When I asked to show it on the local map that hang there, she just pointed at a part that wasn’t highlighted — not even leaving the South of Taiwan. It was very innocent but also very funny. I may have been the first danghashulbu ‘red-hair > foreigner’ that they have every seen in their lives.

Day 3

The daily rhythm continued, and our materials kept growing. However, on this day there was a unique event in the village: a wedding! In these pictures below must be a significant amount of remaining Bununs. Notice the guy who poses for my picture in the second pic below.

Day 4

On the next day we had a field trip in the area. We got to see a family member of the Bunun leader Lāhè āléi 拉荷·阿雷 (1869-1941) who opposed the Japanese occupation of their Bunun territories. And we got the whole story of how this happened.

This was also the spot where I ‘married’ three women at once, an inside joke that followed from my story of how my fortune was told to my by a crone in the Eslite bookstore #truestory. I was going to mary three women in my life, move back to America and would do a host of other improbable things. Here is the picture of the proposal and the result.

Day 5

All good things come to an end. So too our stay with the Bunun. As if the mountain god didn’t want to see us leave it started raining so hard, we had to stay just a bit longer.

But our time there came to and end and I know I will definitely go back to visit them, especially our dear Yan laoshi, or Hanaivaz in Bunun, who is one of the kindest people I have ever met.

Returning to Taipei

After having returned to Taipei, we had to give a presentation on the linguistic topic we were working on in Bunun. In my case, that was nominalization and relativization. And eventually we had to turn that into a term paper, which I made accessible here (I’m welcoming comments!):

All in all, it was wonderful and I really recommend this class to everyone who wants to analyze a new language they have no experience with — a chance that is nearly impossible to get in Belgium in the setting we had it here. Here is a final picture of the group on the mountainside, with the clouds hanging lower because of recent rainfall.