Last time we did this, I showed you what my PLN looked like about a year ago. I advise you to read that first before you continue reading below.

In today’s update I will lay out how I generally go about the processing of research. It’s a kind of habit I’ve been cultivating for a few years now, and it generally does pay off, but it did not come out of nowhere and I might have forgotten some of the sources that influenced me. Since the basic process hasnt’ really changed in the last year, I will first display again the picture from last update:

As you can see, I marked the research process with a purple frame. So, let’s dig into it.

Finding research stuff

In general we can break this first point down into two smaller processes:

- finding the bibliographical records

- finding the record itself to read

Finding bibliographical records

Usually this is the easiest part, because you will find references to what other researchers wrote in a variety of places: books, articles, websites, lectures, classes, by word of mouth etc. If this reference is decent enough, you should have the author, title, year, place of publishing (a publishing house or a journal). If not, well, bummer, but you can use some Google, database, or library magic in the hopes of finding the metadata of the record.

Finding the record itself

My usual go-to practice is going to Google Scholar, which is a very large linked database of existing versions of different articles / chapters (I am going to refer to the thing we are looking for as the paper in the rest of this update). Now, Google scholar is also not without problems. The question remains, however, if your institution has access to the paper you are looking for. Usually that is okay, but for some you may be linked to the publisher, where you have to pay for access to the paper. One of the more recent big issues in academia is the cry for more open-access, and we are still trying to find a viable model that does not waste the people’s tax money, but still keeps things like peer-review alive. A really good model hasn’t been found yet, but I have the feeling we are getting there.

Anyway, assuming you do have access to the paper you want, what to do next — that is the issue at stake in this update. Let’s download the thing!

A reference manager

I think now we come at the heart of this update. One of the better inventions in the last few years is that of reference managers: software you can put your bibliographical records in, and that help you spit out references in the style you want. There are a few options out there:

Of these, Zotero and its spin-off Juris-M are my favourites, because they are open source and just do the job I want them to do. Now, let’s first quickly look at what Zotero can do for you!

If you want to read more about this in a blog post at your own pace, I recommend this piece by Mark Dingemanse, which shows the fundamental usage of the software. I’ll show his presentation here as well:

So, once you get that down and get the basic usage of a reference manager, it is worth remembering that all of the previously mentioned reference managers get the same basic trick done. However, I still like the open source (and thus free) Zotero-like software best, because there are some customisations that will improve its usefulness. Of course, as the noun suggests, these customisations, are, well, custom, and fit my personal style best. What you do with your references eventually remains your business, although I can only hope that you at least reflect on how to optimize it. Let’s see how I customized my Zotero.

Customising the storage place of files

I have a folder on my desktop called papers in which I store all my, well, papers. I suggest you do something similar — it is easy to back up, easy to find and its contents are easily searchable, which is what you want.

Linking the data to a file

In Zotero you can link a bibliographical record to a file, in two ways. Either you reimport the file into Zotero, allowing Zotero to make a copy and store it somewhere in its directory where it is not easy to find. The other option is to link to the file. And since we made a folder with all our files, we know exactly where it is and which file we should link to. Then, as you click, it is super easy to find the paper (still assuming you had access and have a local copy of it).

Renaming the file after metadata

So, after you linked to the file within Zotero, you can go right click on the file itself (within Zotero), and rename the file after the metadata, i.e. the bibliographical record you imported/wrote/adapted. This makes finding data even easier!

The next video basically outlines this approach (although he doesn’t store them in a separate location. Listen to me and not to him!)

Juris-M

Now, actually these days I don’t use Zotero itself anymore, but instead tend to use Juris-M. Why is that? Juris-M is able to handle multilingual support in bibliographical records and since I am dealing with Chinese papers and the occasional Japanese one, it is a very handy feature, that many people can’t believe hasn’t been integrated into Zotero itself yet!

However, all the good things of Zotero still exist in Juris-M:

- magic stick input with ISBN / DOI numbers

- the whole archiving process I briefly outlined above

- plug-ins into Word or .odt files

- online sync to your account

- the superlarge repository of citation styles

So that is the way to handle files. But now, what do I do after I have gotten the bibliographical record and a soft/hard copy of the paper?

Taking notes

I am assuming you are using some kind of note-taking strategy to deal with research. For classes I tend to have a mix of written notes and digital ones, but for research I pretty much put everything in a digital note-taking programme. I’ve been using Evernote since a few years, because of their (back then) really good free plan — recently they’ve limited the free integration on different devices to a whopping maximum of two. But if you do want to use if for free, I would suggest computer and phone, because Evernote has a nice phone camera integration, as well as the ever-so-useful webclipper.

Of course there are alternatives out there, such as MS’s OneNote or the more recent hashtag-friendly Bear etc. I think it’s probably most beneficial to just stick with one, and since I settled on Evernote a few years ago, it’s easy to stay there. However, that doesn’t mean I am completely in love with it: for instance, its continued lack of markdown integration is very annoying, because that is a very efficient way of taking notes. But it must be said, Evernote is a behemoth, and can probably handle virtually all of your note-taking qualms.

Now, let us go back to our topic. Let’s say, you have your paper, did all the bibliographical stuff correctly. Now what? Use Zotero to make a bibliographical reference and put it in the title of your Evernote note. It’s best to make some kind of folder to collect all research notes — mine is called Annotated Bibliography.

Next, you are gonna want to repeat the same line as the first line of the note itself. This is because sometimes you have to shorten the title a little bit, for instance when it is too long because it is a book chapter.

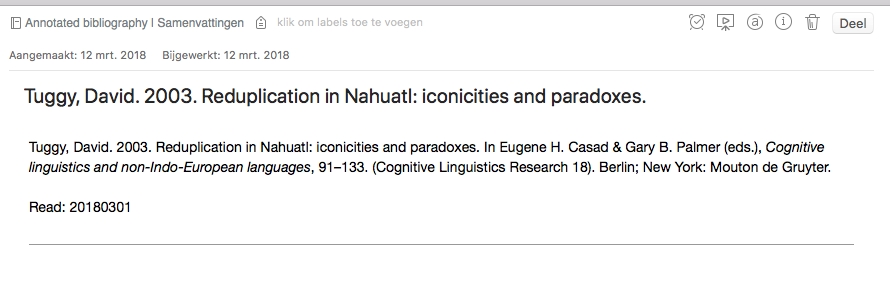

Then, I always put the date I read it, in the order of year-month-day: Read: YYYYMMDD. This is because if you later revisite the note, Evernote might update the record to the new date you did some changes on. So I generally end up with a header that looks like this:

Beneath that line (---) I can start my note itself: what I think are important points, or things I don’t agree with. Usually I will also write some judgment right below the read information, saying if I liked the paper or not. The trick is to allow future me to able to recall the big message of the paper without having to plough through it completely again. However, that also depends on how well you process it the first time. Luckily, note-taking software usually allows for good searching capabilities, to help you find previous notes, and also relate notes you didn’t know where dealing with similar things.

There is also the option to tag them, but I don’t really make use of this feature.

And that is basically it, but then quantified over many papers. I don’t quite remember when I exactly started doing it as follows, but I currently have 233 notes in Evernote and apparently 889 items in Zotero. This reflects my evolution from 2014 or 2015 onwards: going from paper to Zotero to more digital notes.

I hope this has been useful to you (as it was for me — spelling out my process and seeing how it evolved from last year’s workflow). In the next update of this series (Academic Workflow) I am going to discuss R and Rmarkdown.