A few weeks ago I twote this:

Won't say I'm a pro (more like intermediate if even that much ha) but can now say that I am sufficiently familiar enough with @psychopy to build experiments for research on ideophones and iconicity.

— Thomas Van Hoey | 𓏏𓅓𓋴 | 司馬智 (@Simazhi) April 30, 2021

But the learning route has been pretty 𝑘𝑎̌𝑛𝑘𝑒̌ 坎坷.

Because Bonnie McLean asked for a blog about the experience and some general thoughts on the use of PsychoPy, I decided to write it down. So here it is.

WTF is PsychoPy

PsychoPy (Peirce et al. 2019 doi: 10.3758/s13428-018-01193-y) is an application for the creation of experiments in behavioral science (psychology, neuroscience, linguistics, etc.) with precise spatial control and timing of stimuli. There are two ways of creating an experiment: either by writing raw python code, or by using the Builder to get a more GUI experience (to which some code can be appended).

For someone with a more corpus-oriented background (le moi), it was looking like a daunting task to create this kind of experiments for which it was important that the reaction times etc. were controlled for. Note that other software like Qualtrics, or even Google Forms, is still great for surveys for which such control is not super relevant; but it makes sense to think that in psycholinguistics we ideally would want to capture such information in a realiable manner. There’s also a budding psycholinguistic community that is based on the Shiny framework for R, like ShinyPsych, and I know the aforementioned Bonnie is also scripting experiments based on R, although I don’t know if its ShinyPsych.

So, because PsychoPy is supposedly easy to use, open source, and because it can also be deployed on its linked platform Pavlovia to actually run the experiments, it seemed like a good choice to base our experimental work on, especially in times of Covid. However, for the preparation of stimuli and the post-hoc analysis, I still turn to R.

Builder

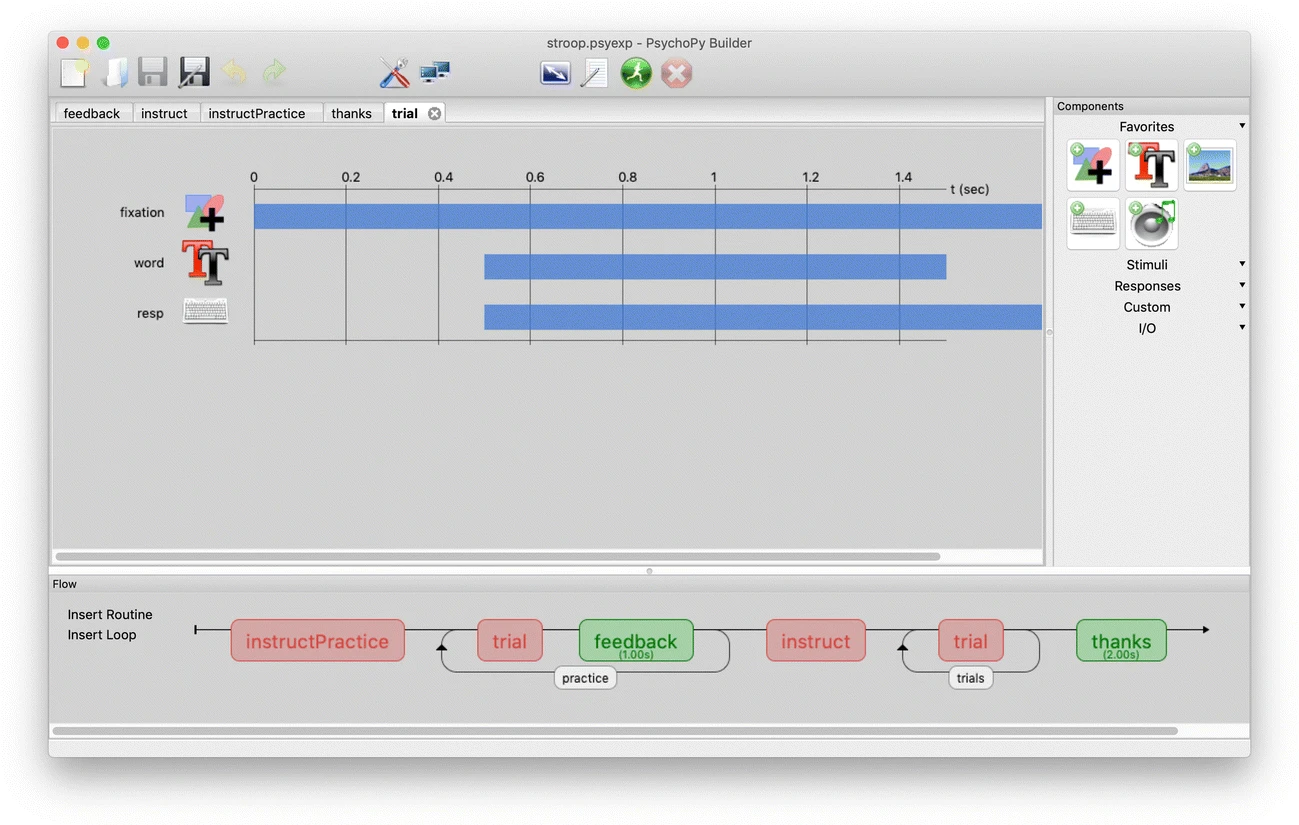

This is what a general PsychoPy experiment in the Builder view looks like.

In the lower box, you can see the different “routines” that make up the experiment. For instance, here you have the instructions ‘instructPractice’, followed by the ‘trial’ and ‘feedback’, which are repeated in a loop. Then you have some new instructions ‘instruct’, followed by the “real experiment” ‘trial’ and a loop again. Finally, a few words of thanks for participating.

In the upper box, you have the uniquely named components of a routine, in this case ‘trial’. You can see that there is a fixation cross present. At some point, a word stimulus will appear. People will have to press a key to respond and then the experiment will go to the next trial in the loop.

So the general buildup is pretty explanatory, and you find heaps of videos on youtube that show the basic anatomy. On of my favorites is the following, on creating a word based reaction time study (watch at your own pace, or as the Japanese say mai peesu de マイペースで):

Following along with such instructional videos can get you up and running pretty fast, although it felt like a struggle because I had to start from scratch. Below I’ll list some things that were not super obvious to me in the beginning. But first, deploying the experiment online.

Deploying and running on Pavlovia

One of the selling points of PsychoPy is the supposed seamless integration with a platform called Pavlovia. You can upload your experiment to this platform, pilot the experiment and finally run it. You do have to pay for running it, but the credits are not very expensive, and you only have to pay for the experiments that are completed; so not for participants that somewhere along the way leave.

Since it was not super intuitive of how to actually deploy the experiment, I once again turned to youtube. Luckily, there were some good demo videos for this aspect as well. My favorite, which helped me the most, is this series by a certain Jordan Gallant:

And now after running the first experiment, I can see say that it works and is accurate enough.

Community

Another aspect that I haven’t touched on yet, is the community. Most people familiar with R or python or what have you know that this aspect is actually quite important. From my mentioning of youtube you can already gauge that there is some vibrancy concerning PsychoPy, but it’s not until you head to https://discourse.psychopy.org/ that you can really find out how thriving it actually is. People will ask questions about errors they face, much like stack overflow, and some of the issues I encountered were indeed answered there (yet not all, spoiler). But so this makes for another compelling reason of why PsychoPy may be a good vehicle for your experiments.

Not very obvious aspects

Here is a series of issues I faced thus far.

1. Which kind stimulus must I use

Perhaps it is because of my background, but it is not always very clear what component of the builder I have to use to get what I want. For instance, figuring out the button or radio boxes is quite hard, and I eventually found other ways of doing it, because I couldn’t figure it out.

2. TextObject is not Text

In the builder you can find two components that seem pretty similar, TextObject and Text. However, they are not the same: TextObject has many more variables you can set, like having a border around your text object (which is pretty crucial in my opinion). While TextObject, at the time of writing, has a small ‘beta’ sticker on top of it, it appeared to me as the new and improved text stimulus go-to. One of the main benefits of TextObject is that the text can be editable, i.e., they can act as small forms. (I don’t know what they did before this function, since that seems pretty crucial??)

But, as the image shows, using TextObject for non-editable text can lead to some weird situation. So better to use a Text component for that.

3. Exporting to HTML

In order to save space or something the default pipeline no longer creates and updates an HTML folder within your PsychoPy folder. However, things would not work for me like that (as opposed to what the forums say), so I had to change my preferences. However, they are not in the preferences, but under the wheel icon.

Then change the path.

Now it will work.

4. Some code functions don’t work on Pavlovia

Once I was finally happy that I had gotten my experiment up and running offline, I was ready to move online. However, some of the handy code components that I had introduced (by following other people’s, as all coders do), didn’t work on Pavlovia. For instance, the quitting function core.quit() does not work; instead you need to replace it with PsychoJS (yes PsychoPy’s own JavaScript implementation) code, like psychoJS.quit().

5. General documentation is not builder focused

I wish the documentation on the website was a bit more visual rather than code-based; as they are promoting this as a “you can build it” kind of software, it was a bit of a hurdle to get over all the technical description of component settings. But it’s not a hurdle that’s too high.

6. Randomization

There are still aspects of randomization I can’t figure out, mostly involving counterbalancing. Perhaps in due time I will find a way to do it.

Other handy resources

Luckily the community is quite good, so there are some documents that help you set up the experiment and “translate” it to Pavlovia.

Two must-reads are:

Conclusion

So all in all I’m quite happy we are using PsychoPy. Having become familiar with the basic functions has enabled me to set up experiments, in such a way that analysis afterwards is clear and reproducible. There is a learning curve, but there is also a supportive community to help out.